Based on official data, German researchers have shown for the first time that only one in seven positive PCR tests in the coronavirus era was actually associated with a coronavirus infection. In an interview with Multipolar, two of them, Michael Günther and Robert Rockenfeller, explain how they proceeded and what hurdles delayed the publication of their paper, which was published in October. The researchers are calling for an “urgent amendment” to the Infection Protection Act, as it has now been clarified that the PCR test produces false figures and is not suitable for detecting an infection on its own.

Source: Multipolar, KARSTEN MONTAG, 4 November 2025

Multipolar: Dr Günther, Dr Rockenfeller, your peer-reviewedresearch results published in October show, based on official data, that 86 per cent of those who tested positive during the coronavirus period were not infected at all. Before we go into the details: Has anyone else discovered and published this before you?

Günther: Definitely not. We analysed German data. So the range of scientists who may have worked on this – including those who work at the RKI or similar authorities – is limited to German-speaking countries. We know from the literature review that no one has cited the ALM data with a numerical value before.

Multipolar: ALM is the “Accredited Laboratories in Medicine“association,which played a key role in diagnostics during the Corona period and whose data they analysed.

Rockenfeller: Even independently of the ALM data, no one has yet determined the quantitative value of the 86 per cent overestimation of infections determined using the PCR tests. There have already been publications that have established that an overestimation has taken place – regardless of the fact that false-positive tests occur and high CT cycles are problematic. However, to the best of my knowledge, no one has ever determined a hard quantitative value of one in seven – i.e. only one in seven people who tested positive was actually infected.

Günther: I haven’t seen our method anywhere in the existing literature either. We have calibrated the PCR tests using the antibody tests. These are two independent series of measurement data. There was a study in Switzerland that analysed both PCR and antibody measurements. However, no quantitative relationship was established between these measurement series.

Multipolar: Based on the same data, you also determined that at the end of 2020, before the coronavirus vaccination was introduced, a quarter of the population had already formed antibodies through contact with the virus, so the vaccination was not necessary for this part of the population. The data you used was not secret for all those years. Is it correct that you are the first to publish this?

Günther: This value is based on empirical data from the laboratories. This is not even the result of our analysis. I read the data in a graph on the ALM association’s website. At the turn of 2020/2021, around 25 per cent of antibody measurements were positive. I found a reference to the ALM website in a letter to the editor of an article on the Nachdenkseiten website. I suspect I was the only one who systematically read these figures. Now they have been saved for posterity and can be downloaded as an appendix to our study.

Rockenfeller: The 86 per cent overestimation of those infected by PCR test is a result of our model adjustment. The positive rate of 25 per cent of all antibody tests at the end of 2020 is actually measured data provided by the ALM trade association.

Günther: We have also saved the webpage in the appendix of the study because the original page no longer exists. It states that the Association of Accredited Laboratories in Medicine, ALM e.V., has been carrying out “structured and standardised data collection in coordination with the authorities at federal level” since the beginning of March 2020. The ALM association apparently set up a limited liability company to collect the data, which operated the project called “Corona-Diagnostik Insights”. The data collection would involve “179 laboratories from all over Germany”, representing around “90 per cent of current coronavirus testing activity from all areas”. The Federal Ministry of Health, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds were explicitly named as partners. It also states that the data was supplied to the RKI and collated there. This means that the RKI, the Ministry of Health and the organisations involved must have seen the data. They were visible in this graphical way – raw, without interpretation and without commentary – for a certain period of time.

Multipolar : If we now assume – as you stated in your study – that only a maximum of one in seven PCR positives was actually infected, what impact does this have on the incidences, hospital cases and deaths that were counted using the PCR tests?

Günther: As a scientist, I would say that there are good reasons why you simply have to divide every number associated with a COVID-19 case or a COVID-19 death by seven. There has also been no systematic investigation in which, for example, the COVID-19 deaths have been confirmed more precisely. According to the RKI, there was only the single criterion of a positive PCR test. It was even irrelevant whether clinical symptoms were present or not. Legally speaking, the PCR test was the only criterion for an infection. This also applies homogeneously to all other epidemiological variables such as incidence or COVID-19 cases. This means that everything that the WHO and other authorities have told us can now be scaled down by a factor of seven.

Rockenfeller: I would like to use the Henle-Koch postulates to emphasise the difference between the PCR test and antibody measurement. Jakob Henle was the doctoral supervisor of Robert Koch, to whom the RKI owes its name. Their work inspired four criteria on how to detect an infectious disease. Namely, that you have to prove where the pathogen is to be found, that you have to grow it in pure culture, that you have to determine something like an invasion and multiplication competence and that you have to detect antibodies. This means that the pathogen must not only be found somewhere and it must not only be clear what kind of pathogen it is. It must also be confirmed that the pathogen has entered the body and is multiplying there in order to prove an infectious disease. As a further step, the body must then form antibodies – i.e. have formed a response to the invasion of the pathogen. This can then be called an infection.

The PCR test only shows where the pathogen is – namely in the mucous membrane, the gateway into the body. The most you can do is try to map the penetration and multiplication competence with the CT value by doubling what you find until the pathogen is detectable. If only a few doubling cycles are required, a lot of virus material was present. If you need many cycles, then there was probably only little material present and the penetration competence was low. The PCR test therefore only detects where the pathogen is located, what type of pathogen it might be and what its penetration competence might be. However, it does not show whether the body has produced antibodies – i.e. whether the pathogen has penetrated and caused an infection. If you say someone is infected on the basis of a positive PCR test – as Christian Drosten did in August 2025 in the committee of enquiry in Saxony – then that is a lie. He knows that himself. After all, he has always written in his publications that a positive PCR test must always be compared with an antibody test in order to determine an infection – for example in a publication on the MERS coronavirus.

Ultimately, that’s also the joke of the coronavirus era. The definition of infections in Section 2 of the Infection Protection Act has not been touched. It states that an infection is present if the organism absorbs a pathogen and it develops and multiplies there. The joke, however, is that proof of this is to be provided by a PCR test. This is stated in the newly added paragraph 22a. Paragraph 2 states that recovery from the disease may only be proven using a PCR test. That is inconceivable.

Günther: That is intellectually inconsistent. There have been antibody tests for viruses since 1942. This has been the standard method for detecting an infection for over 80 years. This is simply being thrown out the window – and wrongly at that. In paragraph 22a, section 3 of the Infection Protection Act, on the one hand, only the absence of an infection – to be proven by a test – is stipulated by law. On the other hand, only a PCR test – encoded by the phrase “direct evidence” – is authorised to prove the absence of an infection. This is perfidious and obfuscating, as it cements the reversal of the burden of proof to the detriment of the individual, and what’s more, with a detection method that – as already mentioned – does not detect an infection.

Multipolar: How did the two series of PCR and antibody tests published by the ALM Association come about?

Günther: The material for the PCR tests is produced from an individual person by taking a swab from the mucous membrane in the throat. Blood is drawn for the antibody tests. The two tests basically also represent the body’s two immune systems – the epithelial and humoral immune systems, i.e. the mucosal immune system and the functionally separate immune system in the blood and lymph vessels.

Multipolar: The PCR tests were carried out to confirm the symptoms of COVID-19, but in many cases also without cause and without symptoms – for example, to allow unvaccinated people to continue working at their workplace. How did the antibody tests come about?

Günther: A GP told me that the trigger usually came from the patient, who for various reasons wanted to know whether they had produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Theoretically, as I said before, you would do a test like this when you make a clinical diagnosis to determine what the disease is. The doctor can then decide how to treat the patient in a targeted manner. The first step is to take a clinical history, which is based on the symptoms. Once the doctor has formed this hypothesis, further differentiation can be made using an antibody test. This is the actual purpose of this test.

Multipolar: In your study, you calibrated the results of the PCR tests using the results of the antibody tests. By calibration, you mean that you compared the two series of measurements from the PCR and antibody tests in order to determine how many of the PCR positives actually produced antibodies – in other words, were actually infected. How are PCR tests and antibody tests related?

Günther: Now we come to the methodology. Let’s start with the 7-day incidence. This measures the positive PCR tests per week. This means that new people with positive PCR tests are added every week. The PCR test is like a snapshot. People may be PCR-positive for a fortnight. Before that, they weren’t and after that, they weren’t. Here, tests are collected for one week, i.e. a snapshot is taken as a weekly value. Antibody measurement in the blood, on the other hand, represents a physiological memory. The measurement of antibodies can be due to an infection two or three weeks ago, two months ago or a year ago. The antibody status at a certain point in time is practically something like a sum of the past. To calibrate the PCR test, I therefore simply have to compare the sum of all positive PCR tests in the past with the positive antibody measurements at the end of a particular week.

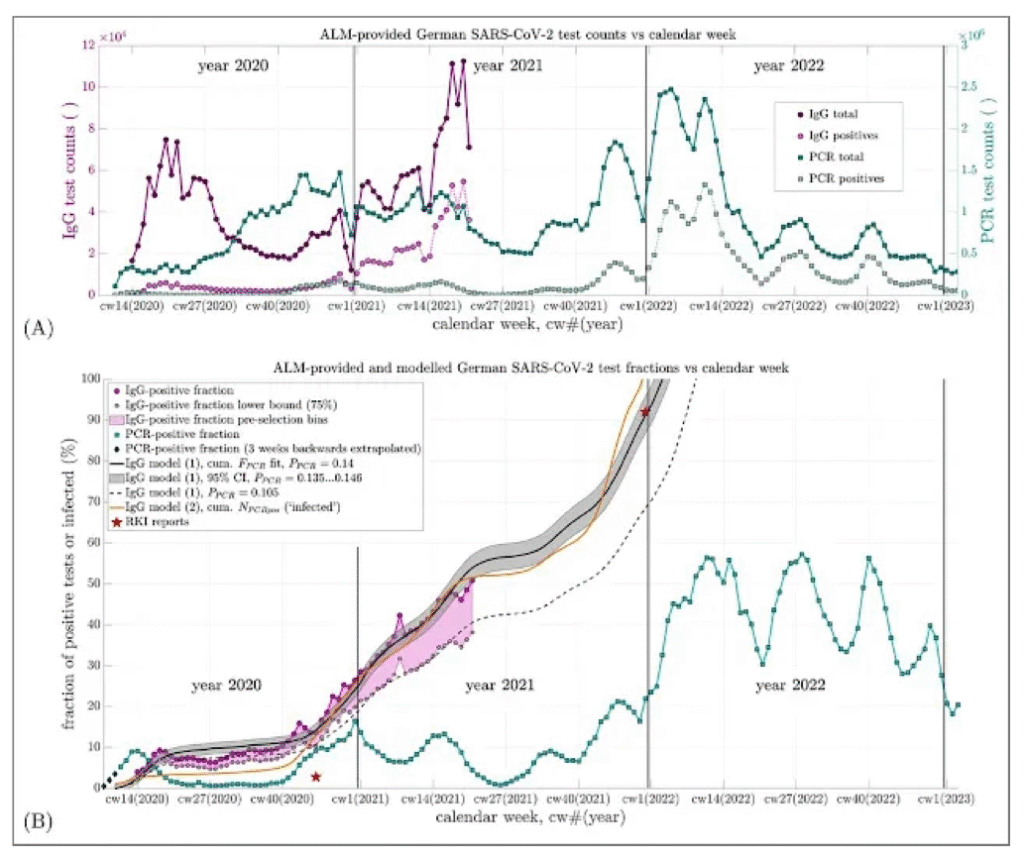

Multipolar: If we look at the diagrams shown in your study, we find the absolute numbers of total tests and positive tests under (A) – whereby you have introduced a different Y-axis for the PCR tests than for the antibody tests due to the different orders of magnitude. Under (B) you have shown the ratio of positive tests to total tests. Can you use the diagrams to explain how you have set the measurement series of the PCR and antibody tests in relation to each other?

Figure 1: (A) German SARS-CoV-2 test numbers provided by the ALM Association plotted over the calendar weeks, (B) German SARS-CoV-2 test proportions provided and modelled by the ALM Association plotted over the calendar weeks, Source: Günther, M., Rockenfeller, R., Walach, H.: A calibration of nucleic acid (PCR) by antibody (IgG) tests in Germany: the course of SARS-CoV-2 infections estimated

Günther: In terms of methodology, we assume that the measurement series from the ALM laboratories were random samples. As a first approximation, we assume that these samples were representative of the German population. Assuming that every positive PCR test is associated with an infection, the summed percentages of positive PCR tests should correspond to the percentage of positive antibody tests at a certain point in time. Then there must be no factor in between. You must therefore add up the weekly percentages of positive PCR tests in Figure (B) – this is the green curve – and compare them with the purple dotted curve. If every positive PCR test indicated an infection, this sum would have to match the purple dotted curve for the proportion of positive antibody tests at each point in time.

Multipolar: However, such a curve would be much steeper than the purple-coloured curve, wouldn’t it?

Rockenfeller: Exactly. If you take all the proportions of positive PCR tests without a minimising factor

added up, we would have already reached a 100 per cent positive antibody test rate in autumn 2020.

Multipolar: If we assume that the PCR tests are a representative sample and that a positive PCR test always means an infection, then by the end of 2020 all people in Germany would have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. This makes the claim that a PCR test always indicates an infection absurd, doesn’t it?

Günther: Exactly. You can put it like that.

Rockenfeller: Of course, we have to rule out the possibility that the majority of people have not been tested twice or three times. In another study, however, we plausibly verified that there were very few duplicate tests up to the summer of 2021.

Günther : If we now assume – as in our modelling – that only 14 percent of positive PCR tests – or every seventh positive PCR test – is accompanied by a positive antibody test, then the black curve highlighted in grey is the sum of the proportions of positive PCR tests. And this corresponds very well in large parts with the respective positive proportion of antibody tests.

Rockenfeller: If we take into account that the antibody sample is somewhat distorted because more people with the disease were tested than those without, then we arrive at a factor of around ten. This is shown in figure (B) by the dashed black line. That doesn’t exactly make it any better.

Günther: Exactly. The dashed curve could therefore theoretically have been the real curve of the population. But if this is the case, then the proportion of positive PCR tests with an actual infection is even lower – namely around one in ten instead of one in seven. The lower the proportion of positive antibody tests, the worse the PCR tests reflect the actual incidence of infection.

Multipolar: You have also indicated two asterisks in the figure. These represent the proportions of positive antibody tests indicated in RKI reports. The second star at the end of 2021 fits very well with your approximation. However, the first star in November 2020 is clearly below the values of the ALM laboratories. The RKI stated that only 2.8 per cent of the population had formed antibodies. How can this discrepancy be explained?

Günther : For a scientist, the most obvious explanation is that there were methodological differences in the measurements. That would be the first thing to look into. We can only say that the ALM laboratories are the most professional. That is certainly recognised. We assume that the ALM laboratories were sent ampoules of blood drawn directly from the bloodstream. The RKI has never taken these measurements. The authority has conducted several studies in this regard. One of them, for example, was to detect antibodies in blood samples. We don’t know which people the blood samples came from. We do not know whether this measurement is qualitatively equivalent to those of the ALM laboratories.

The RKI then commissioned another study in which blood collection kits were sent to participants during the lockdown. The participants then pricked their finger at home and gave a so-called dry blood sample. We cannot judge what influence the different measurement methods have on the result. That would be a question for the professionals in the laboratories who regularly carry out antibody tests. My personal assumption is that these measurement methods were selected by the RKI to ensure low values. I suspect that the downstream measurement methods have led to the distortion.

Rockenfeller: That’s speculation, of course. But if you’re already planning a vaccination campaign in mid-2020 and you want to convince a lot of people to get vaccinated, then you have to argue that the population should be protected as little as possible. A figure of less than three per cent is more convincing than 25 or almost 30 per cent.

Günther: 25 per cent despite the measures! Just by the way.

Rockenfeller: That is of course our interpretation, which can of course also be wrong. But the involuntary release of the RKI protocols has certainly shown that the government’s measures were often not scientifically motivated, but largely politically motivated.

Multipolar: Have you confronted the RKI with the strongly deviating values of the ALM laboratories in the proportion of positive antibody tests?

Günther: No, we didn’t do that. I wouldn’t even know who to contact at the RKI. The data from the ALM laboratories for the two series of measurements for the PCR and antibody tests represent the highest quality that can be expected in terms of methodology. The RKI now has the opportunity to write a so-called “Letter to the Editor” to prove that we have made a mistake. In the peer review process, we were able to convince the reviewers of the validity of the measured values and our results over a year and a half. Our study is basically a provocation to the RKI to find out more background information on these figures.

Rockenfeller: There is another exciting point. In May 2021, the ALM laboratories measured a 50 per cent positive antibody test rate. So the headline at that point should have been that the majority of the population is immune. Instead, the Central Institute of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, for example, said at the time that doctors’ surgeries were “igniting the vaccination turbo”.

Günther: At the end of 2021, when the RKI announced a 92 per cent positive antibody test rate, medical association representatives were saying that we had a “vaccination gap” in order to push for mandatory vaccination.

Multipolar : The publication of the measured values for the antibody tests was discontinued by the ALM association in May 2021, but the publication of the measured values for the PCR tests was continued. What do you think was the background to this decision? Surely the antibody tests were still being carried out?

Günther: I suppose so. It would probably be organised in a market economy. The project funding for the spin-off limited company responsible for data collection would simply be phased out. Then there would no longer be a service provider to summarise the measurement series from the laboratories. The data is obviously available, as the RKI has stated that 92 per cent of antibody tests will be positive by the end of 2021. I expect that the curve of the proportion of positive antibody tests will continue to rise after May 2021, as in our extrapolation in the form of the black line. If we had the actual values for the antibody tests after May 2021, then we wouldn’t even need an extrapolation. Then we would have confirmed the model and its significance would be even stronger. By not publishing the actual measured values, we scientists are deprived of the opportunity to validate our model.

Multipolar: The extrapolation is based on your calibration and is basically the sum of the percentages of positive PCR tests divided by seven?

Günther: Exactly. We have calibrated the model with the available data up to May 2021 and from this point onwards, the black line represents an extrapolation, so to speak, as if the same law would also apply to the subsequent period. And so at the end of 2021, we arrive at the exact value of 92 per cent that the RKI has published.

Multipolar: The peer review process took a little longer for your study. You published the preprint study a year and a half ago. What were the problems with publication in a specialist journal and what were the points of criticism from the peer reviewers?

Günther: We submitted the study to a total of seven specialist journals. Six journals rejected publication – four of these were so-called “desk rejections”. This means that the editor justified the rejection by stating that there were too many submissions, that the topic did not fit into the journal’s spectrum or that the readership already had enough on the topic. Two specialist journals actually also received reviews. Criticism was levelled at these reviews, such as the need to differentiate between genders, age cohorts and premorbidities in the analysis. It was therefore not possible to confirm the conclusions we were drawing. In our view, these justifications merely protected the generally accepted narrative. Our validation of the results with our literature research and with a second model was not addressed at all. The publisher does not authorise the publication of such expert opinions.

At the magazine where the study was finally published, we initially had three reviewers. The reviews took more than three months. The publisher then gave us the chance to respond to their points of criticism. As a result, two of the reviewers resigned. As a result, the publisher had to look for a fourth reviewer because, according to the journal’s guidelines, he is not allowed to accept or reject a study with one review. This took another month. However, we were also able to refute this reviewer’s criticisms.

Multipolar: In your opinion, what should be the consequence of your findings?

Rockenfeller: One consequence should certainly be the urgent amendment of paragraphs 22a and 28a. That should have been done long ago. As already mentioned, paragraph 22a is basically about the fact that only the PCR test can supposedly prove the presence – or absence – of an infection. This is simply wrong. And paragraph 28a defines the concept of 7-day incidence. This is a completely useless nomination per 100,000 inhabitants. Another consequence should be that antibody tests are needed to prove an infection, or even to reveal the difference between acquired and artificially induced immune response. There should also be transparent and comprehensible standardisation of the CT cycles of the PCR test. These are things that have actually been clear for a long time, but are still not reflected in the legal text. This is unacceptable.

About the interview partners: Dr Michael Günther, born in 1964, is a research assistant at the University of Stuttgart. He studied physics and gained his doctorate in natural sciences at the Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen. His area of expertise is the biomechanical modelling of skeletal muscles. PD Dr Robert Rockenfeller, born in 1986, studied mathematics and obtained his doctorate in mathematics at the University of Koblenz. He habilitated there in 2022, also in mathematics. His research interests include biomechanics and epidemiology. He has been a deputy professor for “Stochastics and Statistics” at the University of Koblenz since 2023.